Prospect theory suggests that humans are non-rational decision-makers, and that losses carry a greater emotional impact than gains. It also explains a key reason for inertia in investment decision-making.

Prospect theory is an explanation of human decision-making under conditions where the outcome is uncertain. It can be applied to situations ranging from life decisions, such as whether to switch careers or relocate overseas, through to financial choices such as selecting an investment fund or deciding whether to purchase insurance.

Prospect theory was first defined 35 years ago by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky1, who were subsequently awarded the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics for their research in the field of behavioural economics. Also known as ‘loss aversion theory’, prospect theory suggests that humans are non-rational decision-makers, and that losses carry a greater emotional impact than gains, even where there is no difference in the end result.

For example, most people experience the pain associated with losing $100 more intensely than the pleasure associated with winning $100. Research indicates that the emotional impact associated with a loss is around twice that associated with a gain, meaning that a $200 prize would be required to entice the average person to enter into a 50:50 wager of losing $100.

When it comes to investing, one way to avoid the common pitfalls associated with prospect theory is to invest in a professionally-managed investment fund. Experienced fund managers typically have a disciplined investment process and so are less susceptible to emotional decisions than investors who hold shares directly.

Evolutionary origins

Although prospect theory was defined relatively recently, psychologists believe that the risk aversion associated with the behaviour was developed as an evolutionary survival mechanism. Longevity was maximised by adopting a cautious approach, for example when deciding whether to challenge a neighbouring tribe or expand into unfamiliar territory.

Non-rational decision-making

In addition to highlighting the importance of risk-aversion, prospect theory introduces other concepts that help to explain decision-making:

Reference point is the state of affairs (usually the status quo) that possible outcomes are evaluated in relation to. Investors usually compare the respective gain and loss outcomes separately, rather than considering the final absolute result. This explains the widespread use of rebates and short-term bonus offers, as consumers tend to value these ‘extras’ more highly than identical benefits incorporated in the overall offering.

Decision weight refers to the human bias that distorts probability-based decision-making. For example, we tend to overweight the likelihood of small probabilities (hence the popularity of lotteries) and don’t place enough value on medium to high probability events.

Impact on investment decisions

The biased decision-making associated with prospect theory has a significant impact on investment decisions; yet most of us are unaware that our judgement is clouded.

Consider the following example. Jane must choose between two possible investment outcomes:

- a guaranteed gain of $250

- a 25% chance of gaining $1,000 and a 75% chance of gaining nothing

Jane opts for outcome 1 as she prefers the pleasure of a certain gain over the possibility of receiving nothing.

Market conditions alter, and three months later the two possible outcomes confronting Jane are as follows:

- a guaranteed loss of $250

- a 25% chance of losing $1,000 and a 75% chance of losing nothing

Faced with these alternatives, prospect theory suggests Jane is likely to choose option 2 as she prefers to risk the possibility of a large loss rather than experience the unpleasantness of crystallising a certain loss.

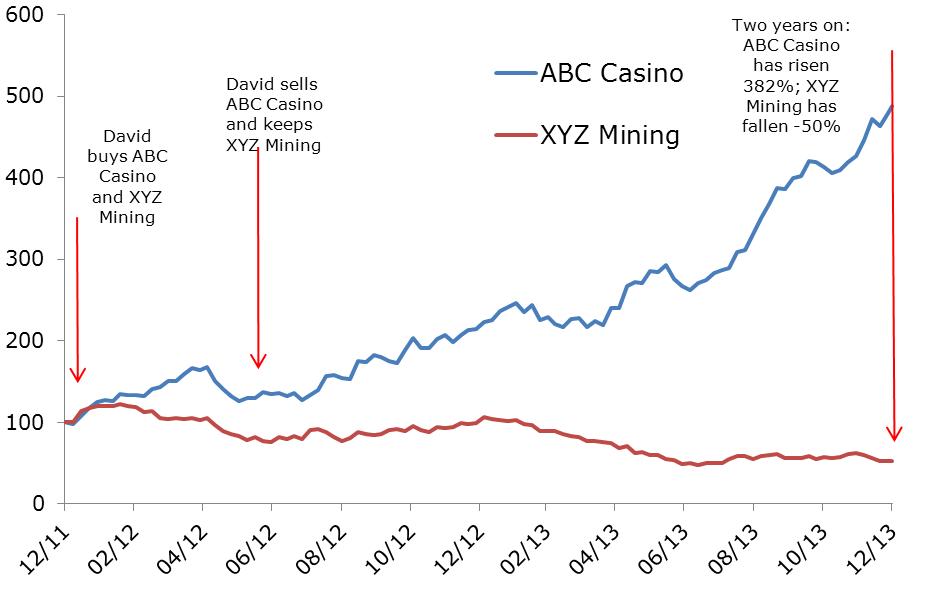

This example illustrates prospect theory’s link to the disposition effect, or the tendency to sell investments that have risen in value, and hold on to investments that have fallen in value. Successful investors are in fact more likely to do the opposite – hold on to appreciating investments while selling their loss‑makers.

Prospect theory also explains a key reason for inertia in investment decision-making. Investors considering a change in investment strategy or a restructure of their stock portfolio are likely to overweight the risks and potential losses associated with the change, and thus opt for the status quo even when the current situation is no longer optimal.

Awareness of prospect theory and its influence on decision making is the first step in avoiding an investment approach clouded by an emotional aversion to losses. However even armed with knowledge of risk-aversion prejudices, investors can struggle to override these ingrained behavioural biases.

A professional investment manager offers a range of products managed according to disciplined investment processes which can help eliminate bias associated with assessment of upside and downside risks.