Understanding Inflation

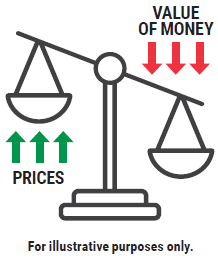

Inflation affects all aspects of the economy, from consumer spending, business investment and employment rates to government programs, tax policies, and interest rates. Understanding inflation is crucial to investing because inflation can reduce the value of investment returns.

What is inflation?

Inflation is a sustained rise in overall price levels. Moderate inflation is associated with economic growth, while high inflation can signal an overheated economy.

As an economy grows, businesses and consumers spend more money on goods and services. In the growth stage of an economic cycle, demand typically outstrips the supply of goods, and producers can raise their prices. As a result, the rate of inflation increases.

If economic growth accelerates very rapidly, demand grows even faster and producers raise prices continually. An upward price spiral, sometimes called “runaway inflation” or “hyperinflation,” can result.

In the U.S., the inflation syndrome is often described as “too many dollars chasing too few goods;” in other words, as spending outpaces the production of goods and services, the supply of dollars in an economy exceeds the amount needed for financial transactions. The result is that the purchasing power of a dollar declines.

How is inflation measured?

When economists and central banks try to discern the rate of inflation, they generally focus on “core inflation,” such as “core CPI” or “core PCE.” Unlike the “headline,” or reported inflation, core inflation excludes food and energy prices, which are subject to sharp, short-term price swings, and could give a misleading picture of long-term inflation trends.

There are several regularly reported measures of inflation that investors can use to track inflation. In the U.S., the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which reflects retail prices of goods and services including housing costs, transportation, and healthcare, is the most widely followed indicator. The Federal Reserve prefers to emphasize the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE). This is because the PCE covers a wider range of expenditures than the CPI. The official measure of inflation of consumer prices in the UK is the Consumer Price Index (CPI), or the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP). In the eurozone, the main measure used is also called the HICP.

Cost-push inflation in context

Both higher oil prices and depreciation of currency have previously caused cost-push inflation,

Example of Higher Oil Prices

Example of Higher Oil Prices

First, gasoline, or petrol, prices rise. This, in turn, means that the prices of all goods and services that are transported to their markets by truck, rail or ship will also rise. At the same time, jet fuel prices go up, raising the prices of airline tickets and air transport; heating oil prices also rise, hurting both consumers and businesses. By causing price increases throughout an economy, rising oil prices take money out of the pockets of consumers and businesses. Economists view oil price hikes as a “tax,” in effect, that can depress an already weak economy.

Example of Depreciation of Currency

Example of Depreciation of Currency

As a country’s currency depreciates, it becomes more expensive to purchase imported goods – so costs rise – which puts upward pressure on prices overall. Over the long term currencies of countries with higher inflation rates tend to

depreciate relative to those with lower rates. Because inflation erodes the value of investment returns over time, investors may shift their money to markets with lower inflation rates.

What causes inflation?

Economists do not always agree on what spurs inflation at any given time, but in general they bucket the factors into two different types: cost-push inflation and demand-pull inflation. Rising commodity prices are an example of cost-push inflation because when commodities rise in price, the costs of basic goods and services generally increase. Demand-pull inflation occurs when aggregate demand in an economy rises too quickly. This can occur if a central bank rapidly increases the money supply without a corresponding increase in the production of goods and service. Demand outstrips supply, leading to an increase in prices.

How can inflation be controlled?

Central banks, such as the U.S. Federal Reserve, European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of Japan (BoJ) or the Bank of England (BoE) attempt to control inflation by regulating the pace of economic activity. They usually try to affect economic activity by raising and lowering short-term interest rates.

Management of the money supply by central banks in their home regions is known as monetary policy. Raising and lowering interest rates is the most common way of implementing monetary policy. However, a central bank can also tighten or relax banks’ reserve requirements. Banks must hold a percentage of their deposits with the central bank or as cash on hand. Raising the reserve requirements restricts banks’ lending capacity, thus slowing economic activity, while easing reserve requirements generally stimulates economic activity.

A government at times will attempt to fight inflation through fiscal policy. Although not all economists agree on the efficacy of fiscal policy, the government can attempt to fight inflation by raising taxes or reducing spending, thereby putting a damper on economic activity; conversely, it can combat deflation with tax cuts and increased spending designed to stimulate economic activity.

How does inflation affect investment returns?

Inflation poses a “stealth” threat to investors because it chips away at real savings and investment returns. Most investors aim to increase their long-term purchasing power. Inflation puts this goal at risk because investment returns must first keep up with the rate of inflation in order to increase real purchasing power. For example, an investment that returns 2% before inflation in an environment of 3% inflation will actually produce a negative return (−1%) when adjusted for inflation.*

If investors do not protect their portfolios, inflation can be harmful to fixed income returns, in particular. Many investors buy fixed income securities because they want a stable income stream, which comes in the form of interest, or coupon, payments. However, because the rate of interest, or coupon, on most fixed income securities remains the same until maturity, the purchasing power of the interest payments declines as inflation rises.

In much the same way, rising inflation erodes the value of the principal on fixed income securities. Suppose an investor buys a five-year bond with a principal value of $100. If the rate of inflation is 3% annually, the value of the principal adjusted for inflation will sink to about $83 over the five-year term of the bond.

Key terms to know

| Commodities: | A commodity is food, metal, or another fixed physical substance that investors buy or sell, usually via futures contracts. |

| Correlation: | A statistical measure of how two securities, such as equities, bonds, commodities, move in relation to each other. |

| Disinflation: | A period of time when economic growth begins to slow, demand eases and the supply of goods increases relative to demand, and the rate of inflation usually drops. |

| Equities: | Ownership or proprietary rights and interests in a company. |

| Fixed Income: | Securities/Investments in which the income during ownership is fixed or constant. Generally refers to any type of bond investment. |

| Hyperinflation: | When economic growth accelerates very rapidly, and demand grows even faster, producers may also raise prices continually. |

| Income: | Money earned on a security from interest or dividends. |

| Maturity: | The date on which a loan, bond, mortgage or other debt security becomes due and is to be paid off. |

| Stagflation: | A period of inflation combined with low growth and high unemployment. |

Source: PIMCO https://www.pimco.com.au/en-au/resources/education/investor-education-understanding-inflation

If you have questions and would like your financial situation to be evaluated, please email us on ds@bluerocke.com with your contacts, for an exploratory meeting, at our cost, not yours.