Introduction

After an event has occurred, people often look back and convince themselves that the outcome was obvious and likely, and that they could have predicted it. This is known as ‘hindsight bias’, or the ‘knew-it-all-along’ effect. In actual fact – particularly in the investment world – outcomes can rarely be reasonably predicted ahead of time.

Hindsight bias is common and can be attributed to our natural need to find order in the world. We create explanations that allow us to make sense of our surroundings, and that help us to believe that events are predictable.

The human ability to find patterns and to link cause and effect can be useful – for example, to a scientist carrying out experiments. However, finding false links between an event and its outcome can sometimes result in unreliable over-simplification.

Studies[1] have also shown that hindsight bias occurs because it’s easier for people to understand and remember the actual outcome than it is to consider the many other possible outcomes that, in the end, didn’t come to pass.

Given how important investment decisions are in our everyday lives, hindsight bias is frequently observed among investors.

Impact on investment decisions

One of the most significant effects of hindsight bias is the way in which it can influence investment decisions.

It does this by encouraging investors to over-estimate the accuracy of their past forecasts. This leads to a false sense of security, causing investors to assume that their future forecasts and decisions will be equally accurate.

As a result, investors often make decisions based on future investment outcomes which may seem obvious and highly likely to them, but actually involve much more uncertainty and risk than they realise.

Philip E. Tetlock, a professor of management at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, has studied people’s tendency to exhibit hindsight bias. “Even after it has been explained to you 100 times, you can still fall prey to the bias” he has said. “Indeed, even after you’ve written about it 100 times.”

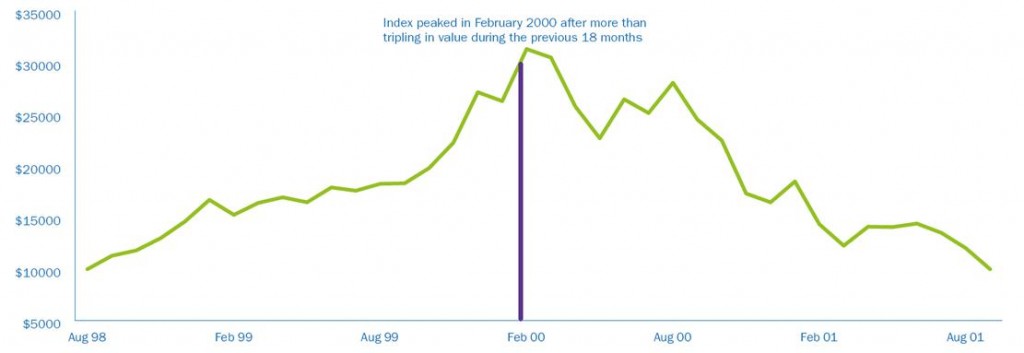

The ability of investors to identify a bubble after it has burst is a classic case of hindsight bias. In both 1999 and 2007, for example, very few investors correctly forecasted that stock markets were about to fall. However, when we now look back at those times, it’s often felt that the signs of what would happen next were clear and there for all to see.

Case study

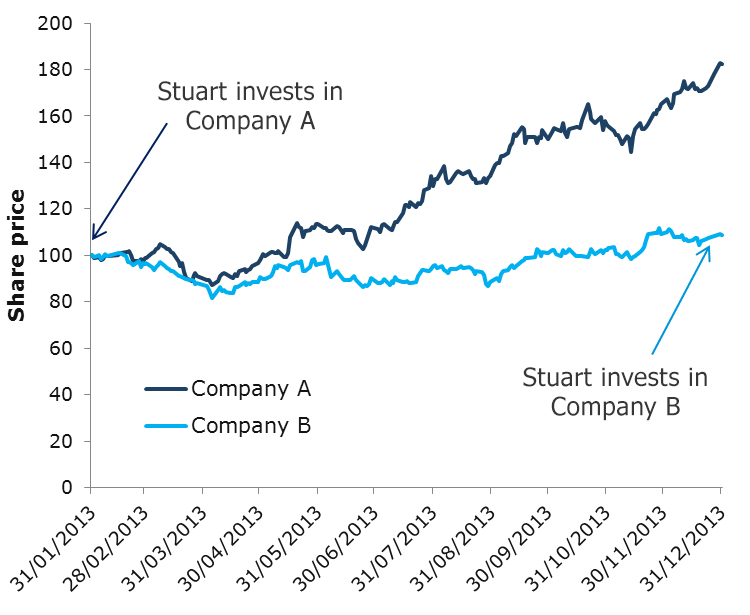

Hindsight bias can be illustrated by the following case study and chart. In this example, our investor Stuart invests in two stocks during 2013.

In January, after much research, Stuart decides to invest in Company A. The share price soon increases substantially in value. Stuart is delighted – his research has paid off! He congratulates himself on his perception and investment insight.

In December, Stuart decides to invest again. His success with Company A gives him confidence that he will be able to pick another winning stock. This time, Stuart invests in Company B.

Of course nobody can be certain how Company B’s shares will perform, including Stuart. But he is more confident in his expected (positive) outcome for Company B – and less focused on the wide range of other possible investment outcomes for its share price – than he might have been before his success with Company A.

In short, hindsight bias has led Stuart to become over-confident in his stock-picking skills.

Illustrative purposes only.

Eliminating hindsight bias

The first rule of avoiding the common investment pitfalls associated with hindsight bias is to be aware that it exists.

Even experienced investors can never be certain how particular investments will perform in the future. Investors must always balance risk and return, placing equal emphasis on all factors that have impacted previous investment decisions, both successful and unsuccessful.

Doing so will provide investors with a clearer and more balanced perspective to their decision-making process. Maintaining this focus can enable investors to avoid the unfounded over-confidence in their predictive abilities that hindsight bias can trigger.

An alternative approach would be to invest in a managed fund, run by a professional investment manager. Investment managers tend to follow consistent, repeatable investment processes which can help eliminate hindsight bias from investment decisions.%